Reviewed by Rabbi Reuven Chaim Klein

The first chapter of this book sets the tone by introducing the reader to the oft-retold story of the famous 17th century false Messiah, Shabbetai Tzvi (1626–1676), and how he and his handler Nathan of Gaza bamboozled much of world Jewry. As the story unfolds, more and more people began to believe that Shabbetai Tzvi was indeed the scion of David sent to redeem the Jewish people, but the story climaxes with Shabbetai Tzvi’s conversion to Islam from which point more and more became suspicious of the dubious character. Although he died in near anonymity and was buried in an unmarked grave, the repercussions of his rise and fall still reverberate throughout Jewish history.

Secret followers of Shabbetai Tzvi, known as Sabbateans continued to exist for centuries after Shabbetai Tzvi’s death. They were known for their antinomian behavior and non-standard Kabbalistic teachings. The witch-hunt against Sabbateans led to one of the most explosive controversies in Jewish History, in which Rabbi Yaakov Emden (1697–1776) accused Rabbi Yonatan Eybeschutz (1690–1764) of being a closet follower of Shabbetai Tzvi. Rabbi Dunner dramatizes this story in Chapter 3 of his book, peppering the narrative with details little-known to those who have already heard about the controversy.

In Chapter 4, Rabbi Dunner tells the sordid tale of a seemingly paranoid man named Isaac Neiberg from Mannheim who divorced his young bride of one week in the town of Cleves and fled Germany. The sordidness focuses not on the young groom, but on the rabbinic controversy that erupted over the validity of this man’s gett (“bill of divorce”). The question centered on what sort of insanity passes the Halakhic threshold to legally disqualify a person from effectuating a divorce.

In his concluding remarks, Rabbi Dunner implies that the ruling that this gett was not disqualified later influenced Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (1895–1986), who ruled that a person who is seemingly mentally unstable in some aspects, but is not totally insane, is not rendered a shotah in Halacha. This reviewer had the privilege to sit on a bus next to Rabbi Meir Simcha Auerbach, a son of Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach (1910–1995), who affirmed that his father whole-heartedly agreed with Rabbi Feinstein’s ruling on this matter.

In his work Mateh Levi (§19), Rabbi Mordechai Horovitz (1844–1910) published a responsum that he ascribed to Rabbi Nosson Maaz (1720–1793), a judge on the Frankfurt court, that laid out the reasons for disqualifying the gett. Nonetheless, some have questioned the authenticity of this responsum by claiming that it was not really written by Rabbi Maaz. Despite Rabbi Dunner’s seemingly neutral position on this question, Rabbi Mordechai Emanuel of Beitar Illit, a renowned scholar who edited and published Rabbi Nosson Maaz’s writings wrote to this reviewer that a comparison of the linguistic expressions used in the responsum published by Rabbi Horovitz and those used in Rabbi Maaz’s recently published-for-the-first-time works reveals that the responsum is most likely authentic.

The common denominator among all the misfits and charlatans that Rabbi Dunner discusses in this interesting book is that each chapter has some connection to the City of London (save for the chapter about Shabbetai Tzvi): In his chapter about the Emden-Eybeschutz controversy, Rabbi Dunner mentions that Rabbi Emden’s father, the esteemed author of responsa Chacham Tzvi, was offered the post of the Chief Rabbi of London, but declined. In the chapter about the Cleves Gett, London appears again as the runaway groom’s destination. (By the way, that story concluded with a happy ending, as the young couple later reconciled and remarried.)

Another chapter focuses on the legacy of the folk-doctor Shmuel Falk (1708–1782), popularly known as the Baal Shem of London. He was reputed to have been a master Kabbalist and healer, and much lore has sprung up about him. Rabbi Emden accused him of being a follower of Shabbetai Tzvi, but that remains to be conclusively proven. Interestingly, for many years a portrait of Shmuel Falk was misidentified as that of the more famous Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem Tov (1698–1760).

Rabbi Dunner also presents the reader with a biographical chapter about the forger Rabbi Yehudah Yudel Rosenberg (1860–1935), who is most known for making the legends about the Maharal of Prague (1512–1526) and the Golem become mainstream, and for publishing a counterfeit commentary to the Haggadah Shel Pesach ascribed to the Maharal. Rabbi Rosenberg also published other forgeries, including a work entitled Choshen Mishpat, which claims that the twelve jewels of the High Priest’s breastplate have made their way to the Belmore Street Museum in London.

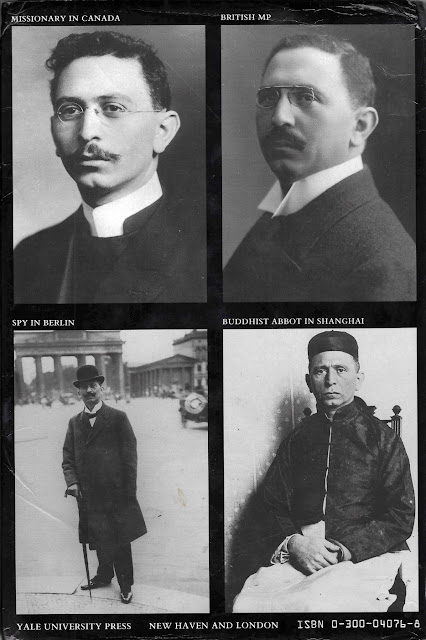

Other chapters in this book that pay homage to London by mentioning the Old Smoke include the one devoted to the peculiar story of Lord George Gordon (1751–1793)—a British aristocrat who led a failed revolt against the English crown (look up: The Gordon Riots) and eventually converted to Judaism—and the one dedicated to the fantastic tale of the escapades of an infamous Hungarian Jew named Ignatius Timotheus Trebitsch-Lincoln (1879–1943), whose various occupations include thief, member of the UK Parliament, international spy, and Buddhist monk. I am fairly confident that all these mentions of London are not unrelated to Rabbi Dunner’s hometown.

Although Rabbi Dunner presents this book to a popular audience and therefore did not provide the reader with well-sourced footnotes for every detail that he discusses (as befits a scholar of his caliber), he did offer a conclusion that sheds light on many of the different sources from which he culled information in preparing this captivating book.

Rabbi Dunner is a scion of a great rabbinic family and an alumnus of the most prestigious Yeshivas of contemporary times. He currently serves as a popular rabbi in Beverly Hills, but is also celebrated as a well-known lecturer, scholar, and social critic. His lectures and essays are thoroughly educational (and sometimes even humorous in his own way) and have special appeal to Jews of all stripes—including Hareidim, Religious Zionists, and even Secular Jews. Rabbi Dunner also boasts a magnificent and impressive collection of Judaica, including rare books, documents, leaflets, and pictures related to the history of the Jewish people. These resources no doubt aid Rabbi Dunner in his scholarly and rabbinic expertise.